Multidimensionaler Aktivismus statt intersektional

Gita Yegane Arani und Lothar Yegane Arani (Prenzel)

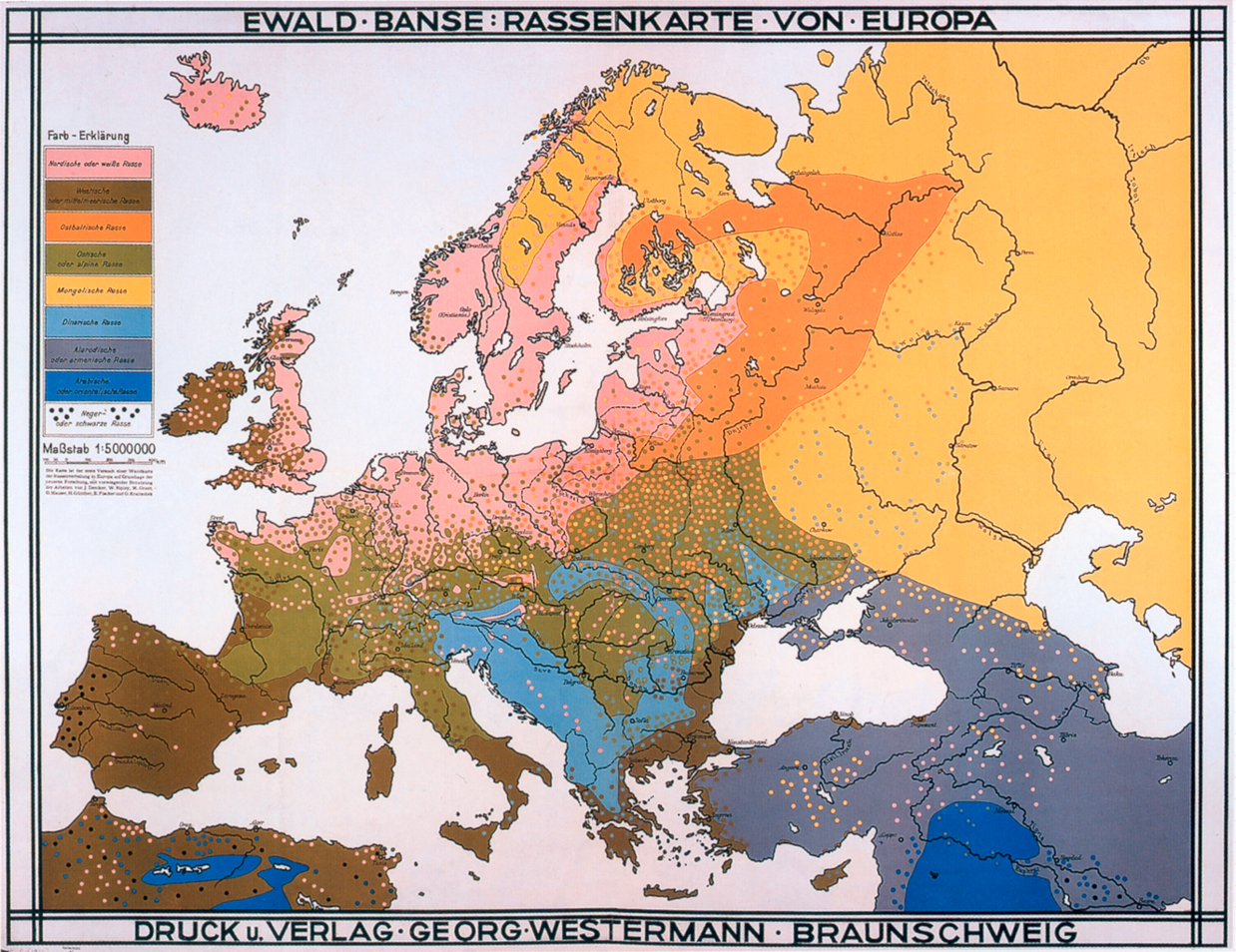

Der Begriff der Intersektionalität wurde im Bereich sozialer Gerechtigkeit und juristisch-soziologischer Analyse von der afroamerikanischen Juristin Kimberlé Crenshaw Ende der 1980er Jahre geprägt. Er diente der Hervorhebung und Adressierung der Problematiken von Diskriminierung marginalisierter Gruppen in der US-amerikanischen Gesellschaft. Die Beobachtung, dass verschiedene Diskriminierungsformen im Bezug auf ein betroffenes Subjekt gleichzeitig und überlappend stattfinden können, wird heute soziologisch häufig beschrieben. Man spricht von Überschneidungen unterschiedlicher Diskriminierungsformen: so zum Beispiel von Schwarzen und (anderen) Menschen aus dem globalen Süden, bei „ethnisch“-argumentierenden Formen von Diskriminierung, von Frauen, von Menschen mit nichtnormativem Gender-Verständnis, von Menschen mit Behinderung aufgrund von „Ableismus“, von Menschen, die durch materielle Armut betroffen sind, usw.

Beim Thema „intersektionaler Veganismus“ werden nun auch Themen mit einbezogen, die die natürliche Umwelt und nichtmenschliche Tiere betreffen.

Klassischerweise beziehen wir die Perspektive von „Sozialsein“ primär nur auf Menschen, und so verstehen manche Menschen unter dem Zusatz „intersektional“ zu Veganismus, allein die sozialen und die politischen Komponenten, die der Veganismus für menschliche Gesellschaften in sich birgt – ungeachtet ihrer Zusammenhänge mit Tierleben und umweltethisch-ökosozialen Aspekten.

Die afroamerikanische Philosophin Syl Ko beschreibt Merkmale, die die Diskriminierungsformen ‚Rassismus‘ und ‚Tierobjektifizierung‘ unterscheiden:

Der Rassismus schließt Menschen aus der Gruppe der Menschen als „Untermenschen“ usw. aus, während die Herabsetzung oder Objektifizierung von Tieren beinhaltet, dass der Mensch sich überhaupt erst gar nicht in relevanter Weise mit dem Tiersein jemals befasst hat, und Tiere diskriminiert werden als ultimativer Ausdruck des Desinteresses und der Unkenntnis von ihnen.

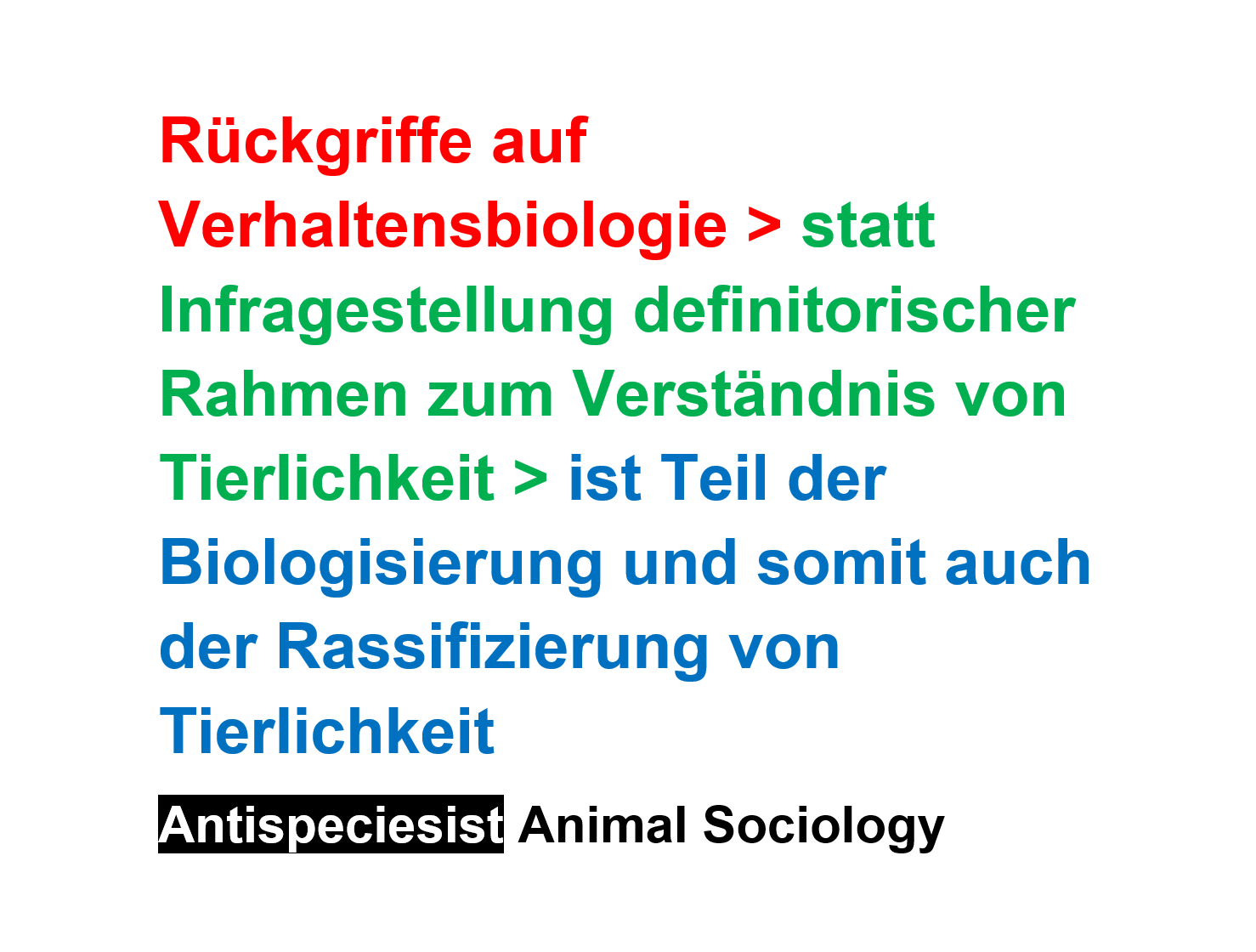

Sie lehnt das Konzept „Speziesismus“ daher in seiner gängigen Form als unzureichend ab, in der man Rassismus, Sexismus, und die weiteren bekannten -Ismen, mit der man intrahumane Diskriminierungsformen unter Menschen beschreibt, nun um den Faktor „Spezies“ als Diskriminierungsfaktor, der sich auf Nichtmenschen bezieht, erweitert. Eine Beschreibung von Tierunterdrückung (Tierobjektifizierung, usw.) sollte, nach Meinung von Syl Ko, in ihrer besonderen Problematik abgebildet werden.

Syl Ko kritisiert ebenfalls am antispeziesistischen Diskurs, wie er gegenwärtig geführt wird, dass allgemein eine Spezies-Objektive Sicht auf Tiere angewandt wird. Dass aber genau der Objektivismus gefahren menschlicher verabsolutierter Perspektivität in sich birgt. Menschliches Verhalten muss sich selbst kritisch hinterfragen und korrigieren können. Syl Ko prägt in ihrem gemeinsam mit der Autorin Lindgren Johnson verfassten Essay: ‚Eine Rezentrierung des Menschen‘ den Begriff der Spezies-Subjektivität als Ort sozialer Interaktion zwischen den Spezies, und entbiologisiert und ent-objektifiziert so die Seite des Tierseins und spricht damit im Sinne einer vernünftigen neuen Tiersoziologie.

Wie geht man mit all den Kategorien sozialer Unterdrückung, sozialen Ausschlusses, sozialen Verkanntseins und mit den globalen Themen ökologischer Zerstörung um?

Die Schwester von Syl Ko, die afroamerikanische Autorin und Aktivistin Aph Ko, mit der Syl das in der Tierrechtsbewegung sehr beachtete Buch ‚Aphro-Ism: Essays On Pop Culture, Feminism, and Black Veganism from Two Sisters‘ im Jahr 2017 veröffentlichte, benennt einen wesentlichen Mangel am Konzept von Intersektionalität.

In ihrem 2019 erschienenen Buch ‚Racism as Zoological Witchcraft‘ schreibt Aph Ko, dass „raw oppressions“ (rohe Unterdrückungsformen) existieren und sie adressiert Unterdrückung nicht vom Standpunkt der Intersektionalität, sondern von der Perspektive einer multidimensionalen Befreiungstheorie aus.

Dazu erklärt sie: „Für eine wahre Befreiung empfehle ich kein intersektionales oder interdisziplinäres Denken: sondern ich ermutige zu einen „un-disziplinären“ Denken. Der einzige Weg, der uns weiterführt, besteht daraus, disziplinäre Logik zu transzendieren. Die Lehrfächer selbst (z.B. über „Rasse“/Rassismus, Gender, Klasse, etc.) sind bereits durch Kolonialität infiziert. Diese sozialen Kategorien sind aus einem unterdrückerischen System selbst hervorgegangen – aus genau dem System, das Aktivist*innen vorgeben zu bekämpfen. Indem sie die kolonialisierten sozialen Kategorien in ihrer „Intersektionalität“ beschreiben, hebt dies jedoch noch lange nicht die Struktur von Kolonialität auf, sondern wir umgehen dadurch lediglich die Arbeit, die wir innerhalb der Kategorien selbst zu erledigen hätten.“ (S.15)

Was viele Akademiker*innen und Aktivist*innen miteinander gemeinsam hätten, sei die bedauernswerte Neigung dazu, „Rassismus“, „Speziesismus“ und andere Gesichter von Unterdrückung als eigenständige zu trennende Themen zu begreifen. Dies zeuge von einer beharrlich bestehenden Kolonialität ihres Denkens. Theoretiker*innen, die sich mit Intersektionalität befassten, so warnt Aph Ko, behaupten, sie würden das Problem lösen, indem sie die Kategorien miteinander in Verbindung setzen. In Wirklichkeit würden sie jedoch das Problem verschlimmern, indem sie die Reifikation der Kategorien selbst zuerst verstärkten.

Was wir anerkennen sollten, so sagt Aph Ko, ist, dass weißes Überlegenheitsdenken (white supremacism) multidimensional zu analysieren ist – das heißt dieser Herrschaftsanspruch drückt sich in verschiedenen Registern aus, einschließlich derer von „Rasse“ und von „Spezies“, die allesamt gemeinschaftlich von Grund auf errichtet wurden.

Ethische Lebensweisen

Eine ethische vegane Praxis kann die kritische Kontextualisierung von Unterdrückungsmechanismen auf Tiere und nichtmenschliche Belange über die Speziesbarrieren hin erweitert thematisieren, siehe dazu beispielsweise in unseren Veröffentlichungen Beiträge von Anastasia Yarbrough, Amie Breeze Harper, Aph Ko und Syl Ko und pattrice jones. Diese Autorinnen stellen in ihren Argumentationen gegen oppressive Systeme unterschiedliche Bezüge zwischen Tierobjektifizierung und Herrschaft her.

Eine Überschneidung von Themenfeldern ist der ethisch-motivierten veganen Praxis vom Grundgedanken her inhärent. Unterschiedliche ethische Felder werden berührt, wobei am zentralsten die Themen im Bezug auf das Mensch-Tier-Verhältnis betroffen sind, weil hier eine Lebenspraxis definiert wurde, die Tierleben in ihren Interessen und Rechten versucht zu berücksichtigen. Der Objektifizierung von Tieren als Vermaterialisierung des Tierseins als Konsumgut wird entgegengetreten. Eine bewusste, achtsame und wertschätzende Ebene der Begegnung von Menschsein mit den Tiersein wird angestrebt. An tierrechtsethische Fragen binden sich ökologische Themen und auch diejenigen Fragen, die all das, was ‚ausschließlich Menschen’ anbetrifft, mit einbeschließen.

Ökologisches Bewusstsein und Gesundheit, als zwei tragende Säulen des Mainstream-Veganismus, sind wichtige gesellschaftspolitische Themen. Im Zusammenhang mit dem Veganismus ergeben sich zahlreiche Schnittstellen perspektivischer Ansätze, das heißt: Die ethisch-vegane Praxis und soziale/politische Positionen stehen in relevanter Korrelation miteinander.

Seit den frühen 2000ern existieren vegane Projekte, die sich solchen Schnittstellen zunehmend aufmerksamer zugewendet haben. Wichtige Themen sind dabei die Nahrungsmittelgerechtigkeit, Rassismus, Feminismus, Sexismus, Homophobie, Ableismus, usw. gewesen. Alle diese Themen wurden durch neue Projekte und Initiativen mit dem Veganismus und aus veganer Sicht kontextualisiert. Solche Projekte bildeten einen Kontrast zu einem veganen Mainstream, der Tier- und Umweltthemen in eher starren konservativen Kategorien betrachtet hat, und in denen eine reduktive Sicht auf Tier- und Umweltthemen oftmals dazu genutzt wurde, Themen intrahumaner Un-/Gerechtigkeit aus der Diskussion herauszuhalten.

Die reduktive Sicht von umwelt- und tierrechtsethischen Fragen gerät erst langsam in Erschütterung durch dekoloniale Diskurse, die imstande sind, klassisch-hegemoniale Kategorisierungen zu hinterfragen.

Organisationen, Gruppen und Initiativen wie beispielweise Sistahvegan und Vegans of Color, einige vegan-feministische und anti-ableistische Initiativen und Blogs oder Projekte, wie Microsanctuaries, die sich Speziessubjektivität zugewandt hatten, sind vegane Projekte dieser Art gewesen. Dort konnten wir erweiterte Perspektivmöglichkeiten in der Ethik sehen, bei denen durch verschiedene Schwerpunkte Akzente gesetzt und Denkanstöße gegeben wurden.

Vermieden werden soll durch die Kontextualisierung von Themenschwerpunkten, dass der Veganismus (und andere, ähnliche ethisch-ganzheitliche Lebenshaltungen) die Chance verpassen könnten ihr politisches Potential dazu zu nutzen, in der breite wirksame erweiterte Ansätze zu schaffen, durch die nichtmenschliche Tiere und die natürliche Umwelt verstärkt mit in den Mittelpunkt ethischer Hauptbelange gesetzt werden.

In allen uns bekannten themenübergreifenden veganen tierrechtsethisch-vertretbaren Projekten spiegelt sich der Gedanke wider, dass eine ethische vegane oder vergleichbare Praxis und Demokratie komplementäre Spieler sind, und dass man sich einig ist, dass hier noch zahlreiche weitere neue Wege beschritten und Möglichkeiten der Verbesserung erschlossen werden müssen.

Die Auseinandersetzung mit Schnittstellen politischer Themen wirkt manchmal wie ein Umweg, um spezifische Fragen herum und indirekt. Die Themenbreite im Auge beizubehalten ist in Diskussionen jedoch wichtig, besonders wenn die involvierten Themen zeitgleich und dringlich in ihren Zusammenhängen behandelt werden müssen. Die Schwierigkeit liegt oft darin, dass sich zwar eine Richtung abzeichnet, in der sich das gemeinsame Übel befindet: Ursachen von Unterdrückung, Zerstörung, Unrecht, Diskriminierung und Gewalt – dass es aber keine Allzwecklösungen gibt für die Unzahl komplexer Probleme, denen sich ein pluralistischer Aktivismus gegenübergestellt sieht.

Eines ist klar: wenn eine Aktivitstin über ihre thematischen Schwerpunkte spricht, seien es Tierrechts-, Menschenrechts- oder Umweltschutzbelange, heißt das nicht immer zwingenderweise, dass das Gesagte auch immer insgesamt weiterzuführen scheint. Vieles an Output, den wir von anderen Aktivist*innen erhalten, sind Dinge, die wir schon oft gehört haben, Dinge die leider nicht immer wieder neu auf ihre aktuelle Gültigkeiten hin überprüft oder upgedated werden, um sich an anderen wichtigen Erkenntnissen im Bereich Aktivismus zu orientieren. Auch stellt die Methodik der Heranführung an Fragen eine Herausforderung und besondere Aufgabe dar, der man sicherlich auch manchmal mit kritischer Selbstreflektion gerechter werden könnte.

Wie weit sind wir bereit dazu, die Rahmen unserer Herangehensweise stetig so zu erweitern, dass sie sich nicht allein auf die bislang mehrheitlich begangenen Wege beziehen, die oftmals zu einseitig und politisch zu wenig innovativ erscheinen?

Dort wo beispielsweise eine Form von Diskriminierung gegen Mitmenschen stattfindet, sehen wir unter Bezugnahme auf Tierrechte und Ökologie, dass Hintergründe von sowohl Unterdrückung als auch Zerstörung weiter zu fassen sind, als wir das bislang mit unseren segregativen Erklärungsmodellen tun. Rahmen müssen dazu neu gesteckt werden und multidimensionale Ansätze sind der einzig gangbare Weg.

Auch wir werden uns im Rahmen unseres ethischen Selbstverständnisses weiterhin nach derart Ansätzen umschauen, wie Tierrechtsethik, Umweltethik und Menschenrechte sich im spezifischen in ihrer wechselseitigen Verwobenheit von ihren Verfechter*innen her als demokratische Elemente mit eingebracht werden: Wie werden Menschenrechte, Umweltfragen und Tierfragen heute aus den Konzepten rausgeholt, die ein neues Denken über diese Kategorien bislang noch zu hindern scheinen? Zusammenhänge aufzuzeigen, führt sowohl zu umfassenderen Fragen, sowie zu umfassenderen und adäquateren Antworten.