Snippets zum Thema: Krönleinnattern und Basilisken – alle Links 5. März 2014

Diese Snippets als PDF (Link öffnet sich in einem neuen Fenster)

Freue dich nicht, du ganzes Philisterland, daß die Rute, die dich schlug, zerbrochen ist! Denn aus der Wurzel der Schlange wird ein Basilisk kommen, und ihre Frucht wird ein feuriger fliegender Drache sein.

Jesaja 14:29

Tierliche Repräsentationen in Mythologien und Folklore:

Krönleinnattern und Basilisken

Im Mythos um die eine Natter mit einem „Krönchen“ finden wir im Wesentlichen zwei Überlieferungsstränge. Einen in der Folklore oral tradierter Märchen und Sagen, und einen in über religiös-beeinflusste Ausläufer bewahrter Mythen. In beiden Richtungen lassen sich die Ursrpünge des Mythos nicht ermitteln, nur weitere Verzeigungen festellen. Doch die Parallelen in den Geschichten sind hier von Interesse.

In dem Mächen von der Unke, aus der Urfassung der Hausmärchensammlung der Brüder Grimm, finden wir den Handlungskern, der deckungsgleich ist mit dem Handlungsablauf (oder „der Moral der Geschichte“) des überwiegenden Teils der Sagen über die „Natter mit dem Krönchen“: Die Natter kann Glück bringen über die, die ihr helfen / Gutes tun.

Die Kinder- und Hausmärchen der Brüder Grimm: Urfassung. Jacob Grimm, Friedrich Panzer – 2008

Die „Kranlnatter“ als Elementargeist

Sagen Niederösterreichs, P. Hillebald Ludwig Leeb, Paderborn, 2011.

Eine Natter mit einem „Krönchen“ – mit vielen Namen benannt

Die Sage über die „Natter mit dem Krönchen“ würde an sich unauffällig bleiben, weil uns das Märchen, hauptsächliche überliefert von Ludwig Bechstein (Das Natterkrönlein, http://www.gutenberg.org/files/23787/23787-h/23787-h.htm#natter), kaum bekannt ist im Vergleich zu anderen populäreren Volksmärchen, aber die folkloristische Überlieferung weist auf eine besondere Rolle dieses tierlichen „Elementargeistes“ hin.

Die Rolle der Natter spielt sich im Bezug auf ihr „Maßtab-Sein“ ab. Der Mensch, der ihr begegnet, kann an ihr versagen und gegen ihr Wohl verstoßen, und er kann ihr Gutes tun und durch sein Helfen von ihr belohnt werden. In ihrem Besitz befindet sich eine kleine Krone, die sie verleihen kann oder die man versucht ihr, der Sage zufolge, zu entwenden.

Die Frage ist: Wie leitet sich solch ein „Tugendbegriff“ von dieser Mensch-Tier Repräsentation in einem Märchen ab? Die Attributisierung des „Maßstab-Seins“ über „Gut“ und „Schlecht“, geht über in einen typischen Tugendbegriff der Märchenwelt.

Krönleinnattern und Basilisken

Einmal saß in Schwarzach ein Kind vor dem Hause und hatte vor sich ein Schüsselchen mit Milch, in die Brot eingebrockt war. Da kroch eine Schlange mit einem Krönele auf dem Kopfe zu ihm heran, aß aus dem Schüsselchen, aber nur die Bröcklein. Da sagte das Kind zur Schlange: „Iß ou Minkle, it bloß Mockle!”

Im Sagenwald, Neue Sagen aus Vorarlberg, Richard Beitl, 1953, Nr. 118, S. 82

http://www.sagen.at/texte/sagen/oesterreich/vorarlberg/beitl/kroenleinnatter.htm

***

Einst versuchte ein vorarlberger Bauer sein Glück, als er an einem Weiher spazieren ging. Die Schlange war baden gegangen, und hatte ihr Krönlein in einer kleinen, ehernen Schatulle am Ufer verwahrt. Der Bauer fand das Kleinod, entwendete es, und rannte so schnell ihn seine Füsse trugen. Dennoch sah er sich bald von zischend züngelnden Schlangen verfolgt: Alle Nattern der Umgebung waren ihrer Königin zu Hilfe geeilt. Da verliess ihn der Mut, und er warf das Krönlein von sich. Er konnte entkommen und gelobte, niemals wieder die Schlangenkönigin bestehlen zu wollen.

http://bestiarium.net/laden.html

***

Haindl, ein verwitweter Bauer, lebte mit seinem Töchterlein allein auf einer Hofstatt. Bisher war es ihm stets gelungen, seine Leistungen an die Herrschaft Marsbach unter größten Anstrengungen zeitgerecht zu erfüllen. Das aber erweckte den Argwohn der Marsbacher Raubritter. „Woher der Haindl wohl das Geld immer nimmt?“ fragten sie sich argwöhnisch. „Vielleicht ist er im Besitze eines geheimen Schatzes?“

Der Bauer wurde unter dem Vorwand, in seinen Leistungen an die Herrschaft in Rückstand zu sein, in den Turm geworfen. Trotz Marter und Pein blieb er stumm. Schließlich wurde sogar seine Hofstatt für verfallen erklärt und sein Kind des Hauses verwiesen.

Noch am gleichen Abend wanderte das Mädchen traurig über die Donauleiten hinaus, um bei Verwandten in Altenhof um Aufnahme zu bitten. Als es über den Waldweg dahineilte, vernahm es einen wundervollen Gesang. Das Mädchen blieb neugierig stehen. Am felsigen Abhang öffnete sich eine Spalte, und heraus kroch eine seltsame Natter. Erschrocken sprang das Mädchen zurück und wollte schnell davonlaufen. Hoch aufgerichtet, das Haupt mit einer leuchtenden Krone geschmückt, hielt die Schlange durch einen Anruft das Mädchen zurück. Die Schlange legte dem erstaunten Kind die Krone zu Füßen und versprach eine Wendung des Schicksals.

„Nimm meine Krone an dich! Sie wird dir allzeit Glück bringen. Verzage nicht, denn auch dein Vater wird bald aus den Händen der bösen Marsbacher befreit werden!“ Sprach’s und verschwand unter wunderschönem Gesang wieder in der Felsspalte.

http://www.hofkirchen.at/hofkirchen31924.htm

***

Die Krönlein-Natter bezieht sich auf eine alte Lechhauser Sage: Früher wuchs auf den Wiesen der Birken-Au ein dichter Auwald, in dem viele Ringelnattern ihre Nester hatten. Die alten Lechhausener sagen: Eine dieser Nattern habe immer ein Krönlein getragen. Sie lebte unter einem Brunnen im Wald und war die Schlangenkönigin. Sie beschützte die Birkenau-Kinder vor Unheil und erfüllte manchmal sogar ihre Wünsche. Heute ist der Auwald in der Birkenau fast gerodet und die Krönlein-Natter wurde dort schon lange nicht mehr gesehen. Aber die Birkenau-Kinder erinnern sich noch an sie: Sie haben an ihrer Schule einen Brunnen aus Muschelkalk, auf dem sich die Krönlein-Natter ringelt, die alle beschützen soll, die an ihr vorübergehen. Vielleicht erfüllt sie dem Betrachter den einen oder anderen Wunsch.

http://de.wikipedia.org/wiki/Birkenau-Grundschule_(Augsburg)

***

Wenn der Geissbube von Herbriggen an den Augen seiner Geissen sah, dass es Mittagszeit war, ging er allemal mit seinem Ranzen an den Bach hinab, um auf einer Steinplatte seinen Imbiss zu verzehren. Und allemal kroch aus einer Felsenritze eine grosse grünschillernde Schlange herzu mit rotem Kamm und einem goldenen Krönlein auf dem Kopf, und er teilte sein Essen mit ihr. Nach der Mahlzeit stieg der Bub ins Bachbett hinunter und trank. Die Schlange folgte ihm und tat desgleichen, legte aber vorher ihr Krönlein auf einem Steine ab.

http://www.markuskappeler.ch/taz/tazs/kroenleinschlange.html

***

Die Schlangenkönigin hat eine Krone. In Teufelskirchen sind sehr viele Schlangen um die Kirche herum. Da hat einer diese Schlange mit der Krone gesehen, und er ist hinaufgegangen, und wenn man ein weißes Taschentuch hinlegt, legt die Schlange die Krone darauf. Und derjenige ist davongegangen, und die Schlange folgte ihm.

Auf das Pflugradl hinauf und die Leitn hinunter, und die Schlange rollte hintennach, sonst wäre er tot gewesen.

Quelle: Zentralarchiv der deutschen Volkserzählung, Marburg, Nr. ZA 184 006. Erzähler: Binder, Ort: Hochwolkersdorf. Erzählt am 12. August 1954 abends im Wirtshaus. Anm: Er hat von seiner Großmutter Geschichten gehört, was er im Zusammenhang mit dieser Erzählung erwähnt.; zit. nach Sagen aus dem Burgenland, Hrsg. Leander Petzoldt, München 1994, S. 246.

http://www.sagen.at/texte/sagen/oesterreich/burgenland/petzoldt/Schlangenkoenigin.html

***

Einmal geht ein Mann an einem Weiher spazieren und sieht auf einem Stein ein eisernes Kistlein, und er geht und hebt höfele das Lid auf, weil es ihn wundert, was in dem eisernen Kistlein sei, und da findet er ein schönes goldis Krönlein drin. Er luget und staunt und will den Augen zuerst nicht recht trauen, nach und nach aber nimmt er das Krönlein zart in die Hand, schaut um, ob ihn niemand sehe, und lauft drauf auf und davon, laufst nicht, so gilt’s nicht. Aber das Krönlein hat einer Schlangenkönigin gehört, die etwa einmal in den Weiher baden gekommen ist, und vor sie in das Wasser gegangen ist, hat sie das Krönlein in das Kistlein gelegt, daß es nicht naß werde. Wie sie aber nach einer Weile aus dem Bad kommt und im Kistlein halt kein Krönlein mehr findet, läßt sie einen lauten Pfiff, und drauf sind viele hundert schneeweiße Schlangen hervorgekommen und wie Pfeile dem Kröneleschelm nachgeschossen. Sie hätten ihn bald erwischt, er ist aber noch so gescheit und verwirft das Krönele und kommt den Schlangen ab. Die sind umgekehrt und haben der Königin das Krönele wieder zur Hand gestellt.

Die Sagen Vorarlbergs. Mit Beiträgen aus Liechtenstein, Franz Josef Vonbun, Nr. 87, Seite 95

http://www.sagen.at/texte/sagen/oesterreich/vorarlberg/walgau/schlangenkoenigin.html

***

Der « Wurmkonig» erscheint auch in Tirol und Vorarlberg. ^) Der «Ottern-könig», der besonders in der Nähe von Grochwitz bei Weida spuckt, ist schwarz und weiß gesprenkelt. Er schenkt oft armen Mädchen die Krone. ^) — Häufiger jedoch verfolgt das m3rthische Thier die Menschen. An der Eisak soll ein «fahrender Schüler» den «weißen Haselwurm» und eine Menge «Beißwürmer» ins Feuer gezaubert haben, bis der «Wurmkönig» (Schlangenkönig mit der Krone) ihn «mitten durchbohrte». Ganz dasselbe erzählt man im Bemer Oberlande. Paracelsus soll den «Haselwurm» gegessen und viel Weisheit in sich aufgenommen haben. — Eine andere Tiroler Sage lässt den Zauberer pfeifen, dass alle Schlangen ins Feuer kriechen, nur der «Wurmkönig» ahmt das Pfeifen nach, umschlingt den Zauberer und rollt ihn ins Feuer. — Ein Theologe aus Brixen wollte den «Beißwürmem» das Handwerk legen. Es kostete ihm das Leben, weil ein weißer dabei war. (Siehe Zingerle, iSgi.p. 182 — 185; femer Schnellers Sagen aus Wälschtirol, Innsbruck 1867, wo die Heiligen genannt sind, welche derartiges Ungeziefer unschädlich machen.) — In Vorarlberg und Salzburg ist dieser Zauberer ein Bergmännchen. — Auch Grimms Sagen und Märchen deuten auf den «Wurmkönig». Das Volk glaubt seit uralten Zeiten an die «Schlangenkönige mit der göttlichen Krone». Wenn sie erzürnt werden, sollen sie «einenMenschen wie einPfeil oder Speer» durchbohren. In Steiermark hat das Thier einen Katzenkopf, nur in Oberbayern und den angrenzenden Gebieten mehrere Füße, daher der Name «Tatzelwurm». Dieser Name hat sich neben dem «Bergstutzen» auch im Salzburgischen erhalten. Im Ennsthal heißt das mythische Thier oft «Büffel», im übrigen Steiermark «Bergstutz»,’) ebenso im Salzkammergute; in Niederösterreich auch «Kraulnatter» (n. Leeb).

[…] In Tirol und Vorarlberg heißt die Ringelnatter allgemein «Krönelnatter». Auch in Niederösterreich bringt sie Glück: Sie hat Hände (mündliche Mittheilung V. U. W. Wald.).

[…] Die «Krönelnatter» in Tirol hat schwefelgelbe, halbmondförmige Flecken. Ober-Bergrath Prinzinger (Salzburg) meint, das Weibchen der Kupfernatter, wenn trächtig, erscheine sehr dick.

[…] Der «Haselwurm» oder eine «weiße Natter»!*) «Weißer Wurm» und «Wisele»: Also ist das «Wisele» allerdings schon- in älteren Zeiten in die Sagen vom Stollwurm und den Schlangen aufgenommen worden. Wir sehen aber, dass die Sage selbst variiert, vermengt und es nicht klar ist, welchem Wesen die Rolle des «Schlangenkönigs» einzuräumen sei.

[…] Ethnographische Chronik aus Österreich. 26 S. Österreich heiße der Bergstutzen Kraulnatter (S. 144 und 153 dieser 2^itschrift). Dagegen bemerke ich: l. Der Name lautet nicht Kraul-, sondern Kranlnatter, d. i. die Natter mit dem goldenen Kranl oder Krönlein. Mein Buch bringt die Erklärung im Sachregister (S. 144). Man sagt übrigens auch Kranzelnatter. 2. Die Kranl- oder Kranzelnatter ist verschieden vom Bergstutzen. Denn erstere hat die Gestalt einer Ringelnatter, ist harmlos, wenn sie nicht gereizt wird, und gilt als die Schlangenkönigin. Letzterer aber ist kurz, dick und schwarz, überfallt sogar Menschen, hat kein Krönlein oder Kranzel und gilt nicht als Schlangenkönig.

[…] 117. Reiterer, C. Die Kronlnatter. Zwei Volkssagen (aus Steiermark). Steir. Sep. 1893. Nr. II. S. 64.

http://archive.org/stream/zeitschriftfrst01wiengoog/zeitschriftfrst01wiengoog_djvu.txt

***

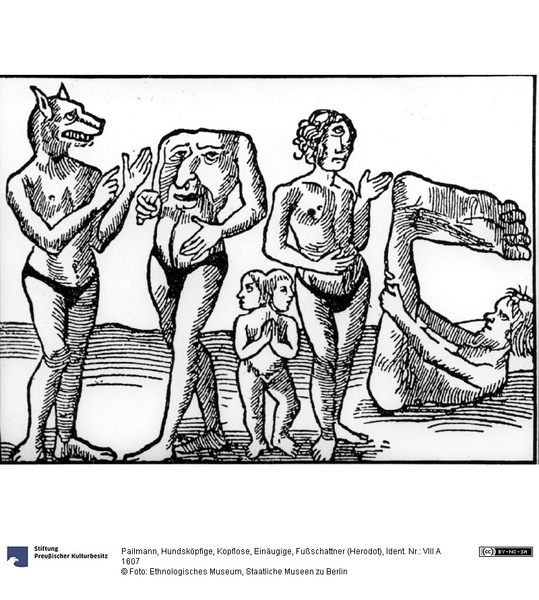

In European bestiaries and legends, a basilisk (/ˈbæzɪlɪsk/, from the Greek βασιλίσκος basilískos, “little king;” Latin regulus) is a legendary reptile reputed to be king of serpents and said to have the power to cause death with a single glance. According to the Naturalis Historia of Pliny the Elder, the basilisk of Cyrene is a small snake, “being not more than twelve fingers in length,” that is so venomous, it leaves a wide trail of deadly venom in its wake, and its gaze is likewise lethal; its weakness is in the odor of the weasel, which, according to Pliny, was thrown into the basilisk’s hole, recognizable because all the surrounding shrubs and grass had been scorched by its presence. It is possible that the legend of the basilisk and its association with the weasel inEuropewas inspired by accounts of certain species of Asiatic snakes (such as the king cobra) and their natural predator, the mongoose. […] The basilisk is called “king” because it is reputed to have on its head a mitre- or crown-shaped crest.

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Basilisk

***

Basilisk. Latin name: Regulus. Other names: Baselicoc, Basiliscus, Cocatris, Cockatrice, Kokatris, Sibilus

http://www.bestiary.ca/beasts/beast265.htm

***

Eine von allen Leuten gemiedene Bettlerin wohnte in einem einsamen Häuschen. Sie trug eine Schlange am bloßen Leib. Einmal wurde sie krank und lag schon 2 Tage ohne Hilfe. Da kam ein mitleidiges Schulmädchen, brachte Essen und wollte um den Bader gehen. “Vergelts Gott” sagte die Bettlerin und starb. Über ihrem Kopf aber streckte sich eine Krönlnatter hervor, verneigte sich und warf dem Kind das Krönl in die Schürze.

Ein armes, frommes Mädchen kam nachts über eine einsame Donauleiten. Da hörte es Gesang, eine Steinplatte öffnete sich und eine Krönlnatter kam hervor und sagte, das Mädchen habe sie nach 400 Jahren erlöst. Sie legte dem Mädchen die Krone zu Füßen und verschwand. Das Mädchen behielt die Krone zeitlebens und hatte immer Glück.

Oberösterreichisches Sagenbuch, Hg von Dr. Albert Depiny, Linz 1932, S. 58 – 60

http://www.sagen.at/texte/sagen/oesterreich/oberoesterreich/allgemein/kroenlnatter.html

***

Dracontia, gimroder ft’. This gloss is discussed by Schlutter, ‘Old English Glogses’, in Journal of Gernianic Philology I 320: ‘gimnaedder’ (or rather naeddergim?), ‘adderstone’ ; on record in theErfurtas well as in the Corpus Glossary. TheErfurthas (C. G. L. V 356, 55), dracontia, grimrodr; the Corpus, D 364, dracontia. giraro. df, that is, gimrodr df = gimnedr dicitur, ‘gern of the adder’; it is the snakestone or ‘Natterkrönlein’ of the fairy tales. Sweet, in his dictionary, exhibits gimrodor, ‘a precious stone’. cp. Corpus Glossary D 365, draconitas. gemma ex cerebro serpentes = C. G. L. IV 502, 14, dragontia gemma ex cerebro serpentis.’

Holthausen answers this in Anglia 21. 242: ‘Wenige dürften zugeben, daß ‘natterstein’ und ‘steinnatter’ dasselbe seien; für Schi, bedeuten sie dasselbe, denn er verwandelt (s. 320. nr. 48) gimrodr (dracontia) frischweg in gimnaedder ‘adderstone’, weiß also nicht, daß das Tier im ae. na-dre heißt! Fragend fügt er nur bei, ,.or rather naedder- gim?” Die Aldhelmglosse gimrodur (Anglia XIII 30, nr. 60) ist dann auch wohl ein Schreibfehler?’

[Vgl.: Wenige dürften zugeben, dass ‘natterstein’ und ‘ steinnatter ‘ dasselbe seien; für Schi, bedeuten sie dasselbe, denn er verwandelt (s. 320, nr. 48) gimrodr (dracontia) frischweg in gimnacddcr ‘adderstone’, weiss also nicht, dass das tier im ae. ndedre heisst! Fragend fügt er nur bei: ,.or rather naeddergim?”^ Die Aldhelmglosse gimrodur (Anglia XEH, 30 nr. 60) ist dann auch wohl ein Schreibfehler?

http://archive.org/stream/angliazeitschrif21tbuoft/angliazeitschrif21tbuoft_djvu.txt]

[Gemrider] gimrodr (dracontia) frischweg in gimnacddcr ‘adderstone’ …

[Drachen / Stein / Himmel-Beziehung, vgl. auch Himmelsgewölbe als grünfarbend und als Stein im Bundahishn, Schahnameh] It is hard to say what is the meaning of this gloss. gim is perfectly intelligible, but rodor means ‘the firmament’, ‘the sky’. It occurs in the Composita beorht-rodor, ^ast-rodor, heah-rodor, süJ)-rador, up-rodor, rodor-tungol, rodorbeorht etc. (Bosworth-Toller), but the meaning is the same in all these cases. What is to be made of it? Although the Word is found seven times, it seems, at least in the case of the Aldhelm glosses, to be derived from one original gloss; the lemraa is to be found in Aldhelm’s Liber de laud. virginitatis p. 15: en ipsius auri obryza lamina. quod caetera argenti. et electri stannique metalla praecellit, sine topacio et carbunculo, et rubicunda gemmarum gloria vel succini dracontia quodammodo vilescere videbitur.

Does the glossator explain Pliny’s (XXXVII 158) or Isidore’s (XVI 14, 7) ‘candore translucido’ by ‘rodor’? Or are we to regard it as a Word only partially understood? Is it possible that beside the idea of the sparkling gem there could have been lurking in the mind of the scribe the idea of the constellation ‘Draco’? In this connection the following quoted by Du Gange is of interest: ‘Draco: Praesertim vero in Anglia Draconis effigie insignitum vexillum obtinuit, ubi ab ineunte fere Regni origine ad haec usque tempora praecipuum inter Regalia Signa habetur, ut olim Auriflamma in Gallia nostra. Draconis Anglicani.

Münchener Beiträge zur romanischen und englischen Philologie. Precious Stone in Old English Literature, Leipzig, 1909.

http://www.archive.org/stream/mnchenerbeitr47erla/mnchenerbeitr47erla_djvu.txt

***

In the Western world the basilisk (little king) has a prominent place in this menagerie. It is one of the earliest—and scariest. The usual description is that its head and feet are those of a rooster, and its eyes those of a frog. Its snakelike body, wings, and speckled pointed tail have strange colors. It kills with its gaze, scorches the earth with its breath, and yet fears roosters and phoenixes. Because it was described in the Bible, most people probably thought it actually existed until the end of the Middle Ages. Now we know better, but it is still with us.

The myth says that the basilisk came from an egg laid by a seven-year-old rooster (when Sirius was high in the sky). The egg was perfectly round and covered by a thick membrane. A toad sat on it for nine years to hatch it.

The basilisk is mentioned several times in the Old Testament. There is no uniform description. It is sometimes described as a snake, but some of its deadly characteristics are mentioned. Isaiah (740–700 BCE), describing how peaceful theLandofPeacewill be, wrote that “a weaned child shall stretch out its hand after the eye of the basilisk.” (Isaiah 11:18)

When 1,000 soldiers in the army of Alexander the Great (356–323 BCE) all died mysteriously at the same time, it was thought that they had encountered a basilisk.

Anna Lantz and Einar Perman, MD, PhD

Stockholm, Sweden

http://www.hekint.org/LV-The-basilisk.html

Abraxas / Anguipede / Gnosis

In a great majority of instances the name Abrasax is associated with a singular composite figure, having a Chimera-like appearance somewhat resembling a basilisk or the Greek primordial god Chronos (not to be confused with the Greek titan Cronus). According to E. A. Wallis Budge, “as a Pantheus, i.e. All-God, he appears on the amulets with the head of a cock (Phœbus) or of a lion (Ra or Mithras), the body of a man, and his legs are serpents which terminate in scorpions, types of the Agathodaimon. In his right hand he grasps a club, or a flail, and in his left is a round or oval shield.” This form was also referred to as the Anguipede. Budge surmised that Abrasax was “a form of the Adam Kadmon of the Kabbalists and the Primal Man whom God made in His own image.”[9]

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Abraxas

Engraving from an Abrasax stone.

***

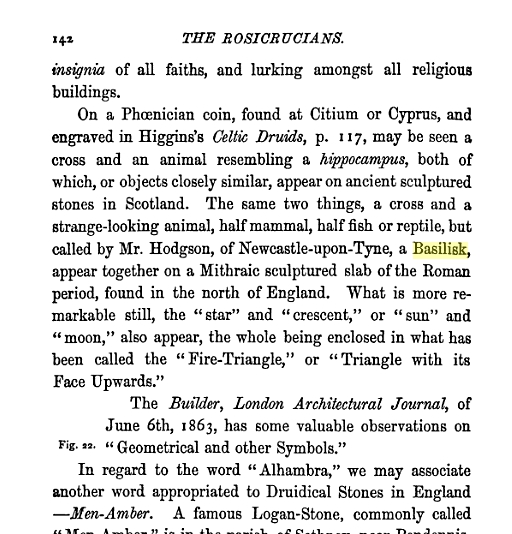

Hargrave Jennings, The Rosicrucians: Their Rites and Mysteries, 1907, S. 142 https://archive.org/stream/rosicruciansthei00jenn/rosicruciansthei00jenn_djvu.txt