More on: Animal Portrayals.

Crime and Punishment by Fyodor Dostoyevsky. PART 1, CHAPTER 5

http://etc.usf.edu/lit2go/182/crime-and-punishment/3396/part-1-chapter-5/

Raskolnikov had a fearful dream […] A peculiar circumstance attracted his attention: there seemed to be some kind of festivity going on, there were crowds of gaily dressed townspeople, peasant women, their husbands, and riff-raff of all sorts, all singing and all more or less drunk. Near the entrance of the tavern stood a cart, but a strange cart. It was one of those big carts usually drawn by heavy cart-horses and laden with casks of wine or other heavy goods. He always liked looking at those great cart-horses, with their long manes, thick legs, and slow even pace, drawing along a perfect mountain with no appearance of effort, as though it were easier going with a load than without it. But now, strange to say, in the shafts of such a cart he saw a thin little sorrel beast, one of those peasants’ nags which he had often seen straining their utmost under a heavy load of wood or hay, especially when the wheels were stuck in the mud or in a rut. And the peasants would beat them so cruelly, sometimes even about the nose and eyes, and he felt so sorry, so sorry for them that he almost cried, and his mother always used to take him away from the window. All of a sudden there was a great uproar of shouting, singing and the balalaïka, and from the tavern a number of big and very drunken peasants came out, wearing red and blue shirts and coats thrown over their shoulders.

“Get in, get in!” shouted one of them, a young thick-necked peasant with a fleshy face red as a carrot. “I’ll take you all, get in!”

But at once there was an outbreak of laughter and exclamations in the crowd.

“Take us all with a beast like that!”

“Why, Mikolka, are you crazy to put a nag like that in such a cart?”

“And this mare is twenty if she is a day, mates!”

“Get in, I’ll take you all,” Mikolka shouted again, leaping first into the cart, seizing the reins and standing straight up in front. “The bay has gone with Matvey,” he shouted from the cart—”and this brute, mates, is just breaking my heart, I feel as if I could kill her. She’s just eating her head off. Get in, I tell you! I’ll make her gallop! She’ll gallop!” and he picked up the whip, preparing himself with relish to flog the little mare.

“Get in! Come along!” The crowd laughed. “D’you hear, she’ll gallop!”

“Gallop indeed! She has not had a gallop in her for the last ten years!”

“She’ll jog along!”

“Don’t you mind her, mates, bring a whip each of you, get ready!”

“All right! Give it to her!”

They all clambered into Mikolka’s cart, laughing and making jokes. Six men got in and there was still room for more. They hauled in a fat, rosy-cheeked woman. She was dressed in red cotton, in a pointed, beaded headdress and thick leather shoes; she was cracking nuts and laughing. The crowd round them was laughing too and indeed, how could they help laughing? That wretched nag was to drag all the cartload of them at a gallop! Two young fellows in the cart were just getting whips ready to help Mikolka. With the cry of “now,” the mare tugged with all her might, but far from galloping, could scarcely move forward; she struggled with her legs, gasping and shrinking from the blows of the three whips which were showered upon her like hail. The laughter in the cart and in the crowd was redoubled, but Mikolka flew into a rage and furiously thrashed the mare, as though he supposed she really could gallop.

“Let me get in, too, mates,” shouted a young man in the crowd whose appetite was aroused.

“Get in, all get in,” cried Mikolka, “she will draw you all. I’ll beat her to death!” And he thrashed and thrashed at the mare, beside himself with fury.

“Father, father,” he cried, “father, what are they doing? Father, they are beating the poor horse!”

“Come along, come along!” said his father. “They are drunken and foolish, they are in fun; come away, don’t look!” and he tried to draw him away, but he tore himself away from his hand, and, beside himself with horror, ran to the horse. The poor beast was in a bad way. She was gasping, standing still, then tugging again and almost falling.

“Beat her to death,” cried Mikolka, “it’s come to that. I’ll do for her!”

“What are you about, are you a Christian, you devil?” shouted an old man in the crowd.

“Did anyone ever see the like? A wretched nag like that pulling such a cartload,” said another.

“You’ll kill her,” shouted the third.

“Don’t meddle! It’s my property, I’ll do what I choose. Get in, more of you! Get in, all of you! I will have her go at a gallop!…”

All at once laughter broke into a roar and covered everything: the mare, roused by the shower of blows, began feebly kicking. Even the old man could not help smiling. To think of a wretched little beast like that trying to kick!

Two lads in the crowd snatched up whips and ran to the mare to beat her about the ribs. One ran each side.

“Hit her in the face, in the eyes, in the eyes,” cried Mikolka.

“Give us a song, mates,” shouted someone in the cart and everyone in the cart joined in a riotous song, jingling a tambourine and whistling. The woman went on cracking nuts and laughing.

… He ran beside the mare, ran in front of her, saw her being whipped across the eyes, right in the eyes! He was crying, he felt choking, his tears were streaming. One of the men gave him a cut with the whip across the face, he did not feel it. Wringing his hands and screaming, he rushed up to the grey-headed old man with the grey beard, who was shaking his head in disapproval. One woman seized him by the hand and would have taken him away, but he tore himself from her and ran back to the mare. She was almost at the last gasp, but began kicking once more.

“I’ll teach you to kick,” Mikolka shouted ferociously. He threw down the whip, bent forward and picked up from the bottom of the cart a long, thick shaft, he took hold of one end with both hands and with an effort brandished it over the mare.

“He’ll crush her,” was shouted round him. “He’ll kill her!”

“It’s my property,” shouted Mikolka and brought the shaft down with a swinging blow. There was a sound of a heavy thud.

“Thrash her, thrash her! Why have you stopped?” shouted voices in the crowd.

And Mikolka swung the shaft a second time and it fell a second time on the spine of the luckless mare. She sank back on her haunches, but lurched forward and tugged forward with all her force, tugged first on one side and then on the other, trying to move the cart. But the six whips were attacking her in all directions, and the shaft was raised again and fell upon her a third time, then a fourth, with heavy measured blows. Mikolka was in a fury that he could not kill her at one blow.

“She’s a tough one,” was shouted in the crowd.

“She’ll fall in a minute, mates, there will soon be an end of her,” said an admiring spectator in the crowd.

“Fetch an axe to her! Finish her off,” shouted a third.

“I’ll show you! Stand off,” Mikolka screamed frantically; he threw down the shaft, stooped down in the cart and picked up an iron crowbar. “Look out,” he shouted, and with all his might he dealt a stunning blow at the poor mare. The blow fell; the mare staggered, sank back, tried to pull, but the bar fell again with a swinging blow on her back and she fell on the ground like a log.

“Finish her off,” shouted Mikolka and he leapt beside himself, out of the cart. Several young men, also flushed with drink, seized anything they could come across—whips, sticks, poles, and ran to the dying mare. Mikolka stood on one side and began dealing random blows with the crowbar. The mare stretched out her head, drew a long breath and died.

“You butchered her,” someone shouted in the crowd.

“Why wouldn’t she gallop then?”

“My property!” shouted Mikolka, with bloodshot eyes, brandishing the bar in his hands. He stood as though regretting that he had nothing more to beat.

“No mistake about it, you are not a Christian,” many voices were shouting in the crowd.

But the poor boy, beside himself, made his way, screaming, through the crowd to the sorrel nag, put his arms round her bleeding dead head and kissed it, kissed the eyes and kissed the lips…. Then he jumped up and flew in a frenzy with his little fists out at Mikolka. At that instant his father, who had been running after him, snatched him up and carried him out of the crowd.

“Come along, come! Let us go home,” he said to him.

“Father! Why did they… kill… the poor horse!” he sobbed, but his voice broke and the words came in shrieks from his panting chest. […]

Photos:

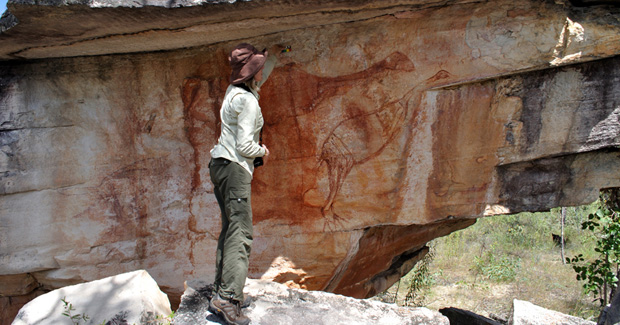

Image 1: Only picture of a live Tarpan, taken in Russia: a stallion caught in 1866, http://www.examiner.com/article/a-wild-horse-recreated-the-tarpan-aka-heck-horse

Image 2: Paolo Troubetzkoy, A Moscow Cabdriver [and “his” Horse] …

Crime and Punishment was published 1866.

Links: 9. March 2014.