Das Geheimnis der Liebe zum Leben

Religiöse Widerständler und heidnische Modernisten

Von Thorm KePa

Dieser Text als PDF (Link öffnet sich in einem neuen Fenster)

Die Katharer waren eine christliche Splittergruppe des europäischen Hochmittelalters, die ihren Glauben an den Gut-Böse-Dualismus der aus Persien stammenden Manichäer des 3. Jahrunderts nach Christus anlehnte. Die Manichäer selbst verbanden unterschiedliche Elemente in ihrem Glauben und so findet man bei ihnen auch eine Anlehnung an das Christentum.

Beide Glaubensgruppen teilten die Vorstellung, dass Tiere nicht geopfert werden dürfen – weder für religöse Zwecke, noch zu Ernährungszwecken. Man geht allerdings davon aus, dass die Katharer Fische aus dieser Vorstellung des (gewollten oder indirekten, religiös verordenten) Lebensschutzes ausschlossen, weil sie meinten, dass sich Fische nicht geschlechtlich vermehren würden und aus dem Wasser entstünden.

Die Katharer glaubten, dass „Lichtteile“ von Engelsseelen ausversehen mit einem toten Tier mitverzehrt werden könnten, und die Manichäer meinten, dass Tiere-Essen hätte zur Folge, dass die „Lichtteile“ des Tieres durch den Verzehr nicht aus dem Tierkörper entweichen könnten. Beide Glaubensgruppen erwarteten eine strenge Befolgung ihrer asketischen Ideale aber nur von der Priesterschaft (bei den Katharern die Parfaits, bei den Manichäern die Electi).

Es gab eine Reihe von Schnittstellen beider Glaubenssysteme, eine davon scheint uns in die Gegenwart zu führen: die Hütung des Geheimnisses irdischer Existenz. Ein Stein bei den Manichäern, ein Gral bei den Katharern.

„Wolfram’s Grail/Stone bears a great resemblance to the Manichaean jewel, the Buddhist padma mani, the jewel found in the heart of the lotus that is the solar symbol of the Great Liberation and which can also be found in the Indian traditions concerning the Tree of Life.” Jean Markale, The Grail: The Celtic Origins of the Sacred Icon, 1999, S. 134.

Beim christlichen Ritter Wolfram von Eschenbach in seinem Parzival taucht der „heilige Gral“, der in der Mystik des Mittelalters für so viele Ritterorden von solch großer Bedeutung war, in der Form des „lapsit excillis / Lapis excilis“ auf:

„Die wehrliche Ritterschaft,

höret, was ihr Nahrung schafft:

Sie leben von einem Stein,

dessen Art muss edel sein.

Ist euch der noch unbekannt,

Sein Name wird euch hier genannt:

Er heißet Lapis exilis.

Von seiner Kraft der Phönix

Verbrennt, dass er zu Asche wird

Und dann der Gluth verjüngt entschwirrt.

Der Phönix schüttelt sein Gefieder

Und gewinnt so lichten Schimmer wieder,

Das er schöner wird als eh.

Wär einem Menschen noch so weh,

Doch stirbt er nich denselben Tag,

Da er den Stein erschauen mag,

Und noch die nächste Woche nicht;

Auch enthellt sich nicht sein Angesicht:

Die Farbe bleibt ihm klar und rein,

Wenn er täglich schaut den Stein,

Wie in seiner besten Zeit

Einst als Jüngling oder Maid.

Säh er den Stein zweihundert Jahr,

Ergrauen würd ihm nicht sein Haar.

Solche Kraft dem Menschen gibt der Stein,

Daß ihm Fleisch und Gebein

Wieder jung wird gleich zur Hand:

Dieser Stein ist Gral genannt.“

Parzival und Titurel: Rittergedichte von Wolfram von Eschenbach, Hrsg. Karl Simrock, Tübingen, 1842, S. 40-41.

Parzival and Titurel. By Wolfram von Eschenbach.

Siehe auch:

Wolfram von Eschenbach: Parzival. Mittelhochdeutscher Text. Hrsg. Karl Lachmann 1833, Berlin

Die Sicht auf den heiligen Gral eröffnet ein Spektrum in dem Inhalte mythischer und religiöser Natur gemeinsam im Universalen zu entdecken sind. Anerkannte „Religionen“ und heidnische „Mythen“ und „Legenden“ lassen sich nicht hundertprozentig voneinander trennen.

Eine andere Parallele, die diese beiden Brückenreligionen, die der Manichäer und die der Katharer, aufwiesen, war ihr Widerstandsgeist der sich gehen die Hauptkirche richtete, der sie sich jeweils entlehnten und durch die sie letzendlich auch vernichtet wurden. Die Manichäer wurden in ihrem Urspungsland Persien vom Zoroastrismus bekämpft, Mani in den Kerker gesteckt, wo er bald starb. Ein Zeungis der zoroastrischen Verachtung des Manichäismus finden wir in diesem Beispiel:

Studia Manichaica edited by Ronald E. Emmerick, Werner Sundermann, Peter Zieme

Die Katharer wurden im qualvoll lang andauernden Albigenserkreuzzug durch die Katholiken final ausgelöscht, nachdem auch die letzten friedlichen Verhandlungen zwischen ihnen und den Katholiken gescheitert waren. Der katharischen Priesterin Esclarmonde de Foix wurde bei diesen Verhandlungen vom später heiligen Dominikus der Mund verboten, sie sei eine Frau, daher stehe es ihr nicht zu sich in einen theologischen Disput einzumischen.

(Vergleiche: Gottfried Koch, Frauenfrage und Ketzertum im Mittelalter: die Frauenbewegung im Rahmen des Katharismus und des Waldensertums und ihre sozialen Wurzeln [12.-14. Jahrhundert], 1962, S. 52 und Giovanni Chiantore, Studi medievali, 1964, S. 748)

Auf dieser Seite befindet sich eine praktische Übersicht über den Verlauf des Albigenserkreuzzugs: http://www.okzitanien.de/historie.htm

Warum sich ausgerechtnet ein christlicher Ritter aus Franken, nämlich Wolfram von Eschenbach, mit einem Geheimnis befasste, dass auch diese beiden Widerstandsreligionen beschäftige, muss mit der geheimnisvollen Popularität des Mythos um den heiligen Gral gelegen haben, der in Europa besonders durch die Arthus-Legende bekannt gewesen ist.

Die Suche und zugleich die Festlegung dessen, worum es eigentlich in dieser Suche nach dem Gral geht (was nun das Abendland und das Mittelalter anbetrifft), ist bis in die deutsche Romantik hineingetragen worden, bedeutungsvoll und mit tiefem Pathos. So band Richard Wagner in seinem Parsifal neue Ideale an die Legende, die bis heute Fragen aufwirft, die für immer unbeantwortbar bleiben müssen.

Richard Wagner, der seinen Parsifal an den Eschenbachs anlehnte, befasste sich zu der Zeit als er dieses, sein letztes Werk schrieb, mit der buddhistischen Lehre der Gewaltsoligkeit gegenüber dem Leben und war fasziniert von der Möglichkeit der „Erlösung“ durch die menschliche Anerkennung der Verantwortung gegenüber dem Leid der Tiere. Er lag damit ganz im Geiste der europäischen vegetarischen Bewegung seiner Zeit.

Auf der Seite der International Vegetarian Union findet man zahlreiche detailierte Biographien von Menschen, die in der vegetarischen Bewegung damals eine Rolle spielten: http://www.ivu.org/

Wagner, der es selbst nicht ganz konsequent bis zum praktiziernden Vegetarier schaffte, schrieb über seine Gefühle der Gewalt Tieren gegenüber:

Richard Wagner an Mathilde Wesendonk (Timokrates Verlag), S. 53

Seine oft zitierte Ablehnung des „Urfalls“ der Gewalt gegenüber Tieren – der biblischen Geschichte über Kain, den Ackerbauenden, der aus Neid seinen Bruder Abel, den Hirten, erschlug, als Gott das Fleischopfer der pflanzlichen Opfergabe vorzog – erinnert intuitiv an die Ablehnung des Alten Testament der Katharer und der Manichäer.

Der Kritik an der jüdischen Tradition seitens Wagners mag damit zusammenhängen. Man will ein Übel an einem vermeintlichen Schuldigen festmachen, an einer bestimmten Lehre, damit man „der Sache“ habhaft werden kann – dabei ist jedes Übel immer an die Fehlerhaftigkeit individueller Menschen gebunden. Wagner wird sich kaum über die Tragweite seiner Kritik bewusst gewesen sein.

Aus Cosima Wagners Aufzeichnungen lässt sich einiges Wichtiges ableiten über das, was ihn zuletzt am meisten beschäftigt haben muss:

Jost Hermand, Freundschaft: Zur Geschichte einer sozialen Bindung , 2006, S. 100.

Wichtig ist es festzuhalten, dass die Suche nach dem heiligen Wahrheitskern auf diesem Pfad, wenn wir ihn denn so verfolgen, so scheint, dass der Lebensschutz bewusst, direkt und unbewusst und indirekt darin zu finden ist. Im Libretto Wagners erfahren wir, dass seine Gestalten im Parsifal von der Heiligkeit des Lebens sprechen:

KUNDRY: Sind die Tiere hier nicht heilig?

[…]

(Vom See her vernimmt man Geschrei und das Rufen der Ritter und Knappen.)

RITTER UND KNAPPEN: Weh’! – Weh’! Hoho! Auf! Wer ist der Frevler?

(Gurnemanz und die vier Knappen fahren auf und wenden sich erschrocken um. – Ein wilder Schwan flattert matten Fluges vom See daher; er ist verwundet, die Knappen und Ritter folgen ihm nach auf die Szene. Der Schwan sinkt, nach mühsamem Fluge, inatt zu Boden; der zweite Ritter zieht ihm den Pfeil aus der Brust. – Währenddem)

GURNEMANZ: Was gibt’s?

VIERTER KNAPPE: Dort!

DRITTER KNAPPE: Hier!

ZWEITER KNAPPE: Ein Schwan!

VIERTER KNAPPE: Ein Wilder Schwan!

DRITTER KNAPPE: Er ist verwundet!

ALLE RITTER UND KNAPPEN: Ha! Wehe! Wehe!

GURNEMANZ: Wer schoss den Schwan?

DER ERSTE RITTER (hervorkommend): Der König grüsste ihn als gutes Zeichen, als überm See kreiste der Schwan, da flog ein Pfeil…

KNAPPEN UND RITTER (Parsifal hereinführend, auf Parsifals Bogen weisend): Der war’s! Der schoss! Dies der Bogen! Hier der Pfeil, den seinen gleich.

GURNEMANZ (zu Parsifal): Bist du’s, der diesen Schwan erlegte?

PARSIFAL: Gewiss! Im Fluge treff’ ich, was fliegt!

GURNEMANZ: Du tatest das? Und bangt’ es dich nicht vor der Tat?

DIE KNAPPEN UND RITTER: Strafe dem Frevler!

GURNEMANZ : Unerhörtes Werk! Du konntest morden, – hier im heil’gen Walde, des’ Stiller Friede dich umfing? Des Haines Tiere nahten dir nicht zahm, – Grüssten dich freundlich und fromm? Aus den Zweigen, was sangen die Vöglein dir? Was tat dir der treue Schwan? Sein Weibchen zu suchen, flog er auf, mit ihm zu kreisen über dem See, den so er herrlich weihte zum Bad. – Dem stauntest du nicht? Dich lockt’ es nur zu wild kindischem Bogengeschoss?

Er war uns hold: was ist er nun dir? Hier, schau her! – hier trafst du ihn: da starrt noch das Blut, – matt hängen die Fluegel; das Schneegefieder dunkel befleckt, – gebrochen das Aug’, – siehst du den Blick? (Parsifal hat Gurnemanz mit wachsender Ergriffenheit zugehört; jetzt zerbricht er seinen Bogen und schleudert die Pfeile von sich.) Wirst deiner Sündentat du inne? (Parsifal führt die Hand über die Augen.) Sag’, Knab’, erkennst du deine grosse Schuld? Wie konntest du sie begehn?

PARSIFAL: Ich wusste sie nicht.

So fast auch der Kulturgeschichtler Jost Hermand diesbezüglich zusammen:

Jost Hermand, Glanz und Elend der deutschen Oper, 2008, S. 139.

Es wird einen Grund haben, warum die Katharer und die Manichäer bis heute dafür bekannt sind, dass sie es als eine Vollendung ihrer Glaubensmission betrachteten in der Askese zu leben, die Gewalt gegen Tiere vermeidet. Und es wird einen Grund haben, warum wir das Motif des Lebensschutzes in anderer Form, aber gebunden an den Mythos der Gralslehre, wieder finden in der deutschen Romantik.

Der Wert solcher Botschaften ist ein fragiler. Der sensible Sinn entweicht schnell denen, die zweifeln an der Möglichkeit des Menschen als transspezies-empathisches Wesen. Aber gerade an dieser Zerbrechlichkeit mag das Geheimnis einer Erkenntnissuche liegen – an dem zu halten, was kaum zu greifen ist, was aber tief in das Herz führt. Weder Religion noch wahre Kunst ist ohne Sensibilität und Reverenz für das Leben denkbar und wenn sie diese nicht aufweisen, werden sie zu Zerstörern.

Es geht hier nicht darum, ob ein Mensch, der durch sein Talent und sein Schaffen besonders hervorragt, nun mit gutem Beispiel voranging und wie genau. Wagner schaffte es selbst nicht ganz hin zum zumindest dauerhaft gelebten Vegetarismus, aber er bemühte sich um eine Botschaft des All-Lebensschutzes, die die Forderung beinhaltete, dass Tiere nicht gejagt, gegessen, getötet werden dürften. Worum es geht ist, dass die Erinnerung und das Bewusstsein über Zeit und Geschichte hinweg erhalten bleiben. Das besondere ist, von welchen Seiten her Fragen aufgeworfen wurden am menschlicher Töten von Tieren für den Fleischverzehr und für das Opfern, gleichwohl wir Zeugnisse dieser Art in den Irrgärten menschlicher Überlieferung nur wie Fragmente zusammentragen können.

So existierte der Manichäismus beispielsweise in einer Zeit, in der er als ‚Lichtreligion’ schon durch eine innere menschliche Spaltung zwischen einem absolut Guten und einem absolut Bösen belastet war. Hier konnte man die Sinnlosigkeit und die ethische Verwerflichkeit der Verursachung von Leid durch den Menschen als eine eigene Verantwortlichkeit, der im menschlichen Handeln Rechnung getragen werden muss, nicht mehr ohne Weiteres thematisieren, denn sowohl die Macht des Bösen, als auch die des Guten waren so gewaltig, dass das eigene Handeln nicht mehr als ein dienen oder gehorchen (der einen oder der anderen Seite) sein konnte.

Dort wo Mensch und Tier in ihrer Problematik und in ihrer Heiligkeit ihres Lebens als Eins genommen werden, wird es für uns aber immer schwierig bleiben das anhand der weltanschaulichen Hinterlassenschaften solcher kulturellen Begebenheiten nachweisen zu können. Zum einen wird man hier keine direkte Hervorhebung der Tierproblematik finden, zum anderen, gehen wir zu stark davon aus, dass alle menschlichen Lebensvorstellungen im Bezug auf die Mitwelt eigentlich ähnlich gewesen sein müssten wie unserer heute.

St. Augustinus , der erst begeistert vom Manichäismus war, wendete sich später von ihm ab in Empörung und überlieferte uns in seiner Kritik viel über die Gründe, warum die Manichäer Tiere nicht töten, opfern oder essen wollten: http://books.google.de/books?id=lHZPAAAAYAAJ&redir_esc=y, + http://www.animalrightshistory.org/animal-rights-antiquity-ce/mani/mani.htm)

Im persischen Mythos gibt es den Humaay / Homa, den Phönix, der im Schahnameh und im iranischen Schöpfungsmythos auch Simorgh genannt wird, in prominenter Weise. Dieser mythische Vogel trug im gesamten Kulturraum zahlreiche, fast unzählige Nahmen, denn er stand für ein Seins-Prinzip.

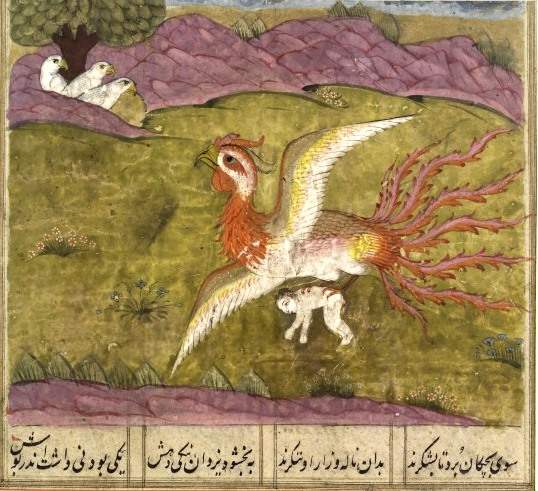

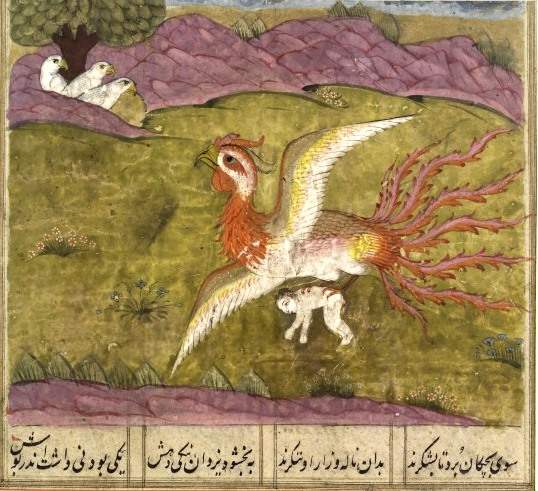

Abbildung, Miniatur eines unbekannten Künstlers aus dem Schahnameh von Firdausi: Simorgh trägt das Kind Zal zu seinem Nest um es vor dem Tode zu retten.

Die bekanntesten Erzählungen über diese Vogelgestalt ist die von Farīd ad-Dīn ʻAṭṭār: The Conference of the Birds und die des im Gebirge nistenden Vogels Simorgh, der das ausgestzte Kind Zal rettet und aufzieht, im Schahnameh von Firdausi.

Nach der Vorstellung im iranischen Mythos teilte sich das Sein in drei Bereiche auf:

1. Die verletzliche Leiblichkeit auf dieser Erde, die „Tankard“; der Raum der Sichtbarkeit und Greifbarkeit.

2. Gab es den Bereich des Sichtbaren aber Ungreifbaren, der durch Simorgh dargestellt wurde. Simorgh konnte nur auf der Erde verletzt werden, aber auch niemals ‚getötet’ werden, sie war der Vogel der Wiedererstehung. Sobald sie vom Boden abhob, konnte man sie auch nicht mehr verletzen.

3. Und es gab den Bereich des Unsichtbaren und Ungreifbaren, den Bereich der Gottheit Vohuman, in der das Sein überging, wenn es auf der Erde verletzt wird und sich nicht mehr schützen kann.

Diese drei Bereiche waren untrennbar Verbunden. In dem Buch: Das Denken beginnt mit dem Lachen: die unsterbliche Kultur der Iran von M. Jamali und G. Y. Arani-May wird der Mythos des Simorgh in seinem Kontext erörtert. Das Buch ist hier abrufbar.