Die zerstörende Gewalt. Der Überlaufeffekt oder die Einmaligkeit in der Vorkommnis von Gewalt?

Zum Holokaust- und Genozidvergleich in der Tierrechtsdiskussion

Vorab: Braucht die Situation des Mensch-Tier-Verhältnisses einen Vergleich zu menschlich intraspezifischenen Situationen zur Hervorhebung von moralischer Relevanz? Wenn nicht, wozu dann die Genozidvergleiche in bezug auf die Situation des Verhältnisses menschlich-destruktiven Verhaltens gegenüber nichtmenschlichen Tieren?

Das Hauptargument, das gegen Genozidvergleiche vorgebracht wird, liegt im Punkt der Unantastbarkeit der Würde des Menschen. Eine ausschließliche Zurückführung auf den Begriff der Würde, kann, als ethisches Kriterium, aber nicht zur Ableitung einer einseitigen moralischen Gewichtung angeführt werden, ohne dass dabei eine Abwertung der Problematik der Gewalthandlungen gegen nichtmenschliche Tiere vollzogen wird.

In der Unantastbarkeit der Würde des Menschen und dem Problem der Verbrechen gegen die Menschenwürde (gegen die Menschheit oder einen Menschen) liegt keine zwangsläufige ethische Implikation im Bezug auf das Verhältnis des Menschen zu seiner Außen- oder Umwelt, die zu einer allgemeinen Begründbarkeit von Gewalt gegenüber nichtmenschlichen Tieren führbar wäre oder diese Formen von Gewalt ausdrücklich und in jedem Fall sanktionieren würde.

Der Begriff der Würde kann, gesehen vom Standpunkt der Meinungsfreiheit, auch nicht strikt in seiner Gebundenheit reduziert werden, ohne dass man dabei das Recht auf freie Meinungsäußerung verletzen würde. Dass heißt, dass eine Auffassung eines Menschen über das Vorhandensein der Würde der nichtmenschlichen Tiere – solange er dadurch keinem Menschen schadet, oder Menschen oder einem Menschen dadurch Gewalt antut – in den Bereich seiner Gedankenfreiheit oder seiner freien Meinungsauffassung fällt.

Menschen werden auch als Opfer und auch als Täter als Würdewesen betrachtet, deren Würde man in den Fällen von Morden und Genoziden brechen wollte; zumindest wurde dies in der Menschheitsgeschichte immer wieder versucht.

Tieren wurde in der Menschheitsgeschichte von keiner Gesellschaft eine Würde einer Unantasbarkeit ihres Tierseins zuerteilt. Damit ist die Besonderheit der Tragweite ihrer Opferposition nicht problemlos mit derer menschlicher Opfer zu vergleichen.

In jeder Situation, in der ein Gewaltverübender ein Opfer schafft, wird man in der Auseinandersetzung mit dem Problem oder dem Fall, Parallelen zu anderen Gewaltsituationen ziehen. Bei Gewalt an sich, unabhängig von der dadurch betroffenen „Angriffsfläche“ oder dem geschaffenen Objekt von Gewalt, kann man vermuten, dass die Motivationen (Destruktivitätswillen, -bereitschaft, gewaltbereite Eigenbezogenheit, Aggression) im Täter übergreifend ähnlich strukturiert sein können, auch weil das letztendliche Ziel oder intendierte Ergebnis von Gewalt: der Mord, die Tötung, d.h. die Zerstörung eines Opfers ist.

Nun verhält es sich aber so, dass die Frage, warum ein Täter sich ein spezifisches Opfer oder eine spezifische Opfergruppe sucht, ganz unterschiedliche Gründe in sich birgt. Auch ist die konkrete Qualität oder Struktur von Gewalt ein maßgeblicher Faktor, der auf die zugundeliegenden Ursachen von Gewalt und die spezifische Gewaltpsychologie zurückschließen lässt.

Produziert gegalt gegen Tiere, Gewalt gegen Menschen? Wenn nicht, warum bestehen dennoch Zusammenhänge in der Gewaltpsychologie

Die Unterscheidungen im Täter-Opfer Verhältnis zwischen potenziellen Opfern, und die Überlappungsmöglichkeiten in der Gewaltbereitschaft ihnen gegenüber, läge in der Frage des sogenannten Spillover-Effekts (Überlaufeffekts):

Die Frage ist, wenn ich dem einen Opfer etwas antue, bin ich dann automatisch auch einem oder mehreren anderen potenziellen Opfern gewaltbereit gegenüber?

Und, dem gegeüberliegend: hat das eine Opfer von Gewalt automatisch dadurch, dass es zum Gewaltopfer wurde, etwas mit einem anderen Opfer einer Form gewaltbereiter Handlung grundlegend gemein, außer dass beide in einer Position des Opfers sind? Liegt irgend etwas auf der Seite des Opfers, das die Gewaltbereitschaft eines Täters auf sich zieht?

Robert Nozick hat die Frage des sogenannten Spillovers vor dem Vordergrund des Mensch-Tier Verhältnisses in der Form beschrieben:

‘[…] Manche sagen, dass Leute nicht so handeln sollten, da solche Handlungen sie brutalisieren und sie die Wahrscheinlichkeit bei der Person erhöhen, das Leben anderer Personen zu nehmen (wir können hinzufügen “oder andererweise zu verletzen”); allein aus der Freude daran. Diese Handlungen, die moralisch nicht an sich in Frage zu stellen sind, sagen sie, haben einen unerwünschten moralischen ‘spillover’ (Überlaufeffekt). (Dinge wären dann anders, wenn es keine Möglichkeit für solch einen ‘spillover’ geben würde – zum Beispiel für die Person, die von sich selber weiß, dass sie die letzte Person auf der Welt ist.) Aber warum sollte es da solch einen ‘spillover’ geben? Wenn es an sich völlig richtig ist, Tieren in irgendeiner Weise etwas anzutun, aus irgendeinem Grund, welchem auch immer, dann, vorausgesetzt eine Person realisiert die klare Linie zwischen Personen und Tieren, und behält dies in ihrem Kopf während sie handelt, warum sollte das Töten von Tieren dazu neigen, sie [die Person] zu brutalisieren und die Wahrscheinlichkeit erhöhen, dass sie [andere] Personen verletzen oder töten könnte? Begehen Metzger mehr Morde? (Als andere Personen die Messer in ihrer Nähe haben?) Wenn es mir Spaß macht einen Baseball fest mit einem Baseballschläger zu schlagen, erhöht dies in bedeutender Weise die Gefahr, dass ich dasselbe mit jemandens Kopf tun würde? Bin ich nicht imstande dazu, zu verstehen, dass sich Leute von Basebällen unterscheiden, und verhindert dieses Verständnis nicht den ‘spillover’? Warum sollten Dinge anders sein im Fall von Tieren. Um es klar zu sagen, es ist eine empirische Frage ob ein ‘spillover’ stattfindet oder nicht; aber es besteht ein Rätsel darüber, warum es das tun sollte.’ (1)

Diese Unterscheidung wird im Falle von nichtmenschlichen Tieren in auffallend deutlicher Weise vollzogen (Speziesismus). Ein Tier physisch zu schädigen oder zu zerstören, es zu töten, verhält sich im Rahmen unserer Gesetze als Sachbeschädigung, nicht als Körperverletzung oder Mord; während das Opfer-werden beim Menschen durch soziale, ethische, religiöse und gesetzliche Konstrukte eine andere Bewertung erhält.

Im Bezug auf Genozide kann man also sagen, die Menschen, die zum Opfer wurden, wurden vor diesem Hindergrund betrachtet, bewusst zum Opfer gemacht. Sie wurden bewusst aus dem ethischen und gesetzlichen Rahmen gewaltsam hinausbefördert.

Anders verhält sich die Situation der nichtmenschlichen Tiere in ihrer Rolle im Rahmen der spezisitischen und homozentrischen menschlichen Beurteilung. Wie schon gesagt gilt die Körperverletzung nichtmenschlicher Tiere nicht oder kaum als „Verletzung“, da die ethische Klassifizierung nichtmenschlicher Tiere, deren Leidenskapazitäten und damut auch deren Würde, bislang nicht mit im Rahmen der Verpflichtungen ethischen Sozialverhaltens ansiedelt. Wobei wir es hierbei tatsächlich mit einem neuen Komplex der Ethik zu tun hätten, dem Interspezies-Sozialverhalten. (2)

Die ganze anthropologische Konstellation einer homozentrisch ausgerichteten Welt, muss in ihrer Konkretheit untersucht und überdacht werden. Analogsetzungen reichen nicht, um hier zu einer ethisch-moralischen Lösung zu gelangen. Wegen der konkreten Beschaffenheit, aus der sich die diskriminatorische Haltung gegenüber der autonomen Bedeutung nichtmenschlicher Tiere zusammensetzt – aus dem Grund der ganz speziellen Form von Gewalt in diesem Fall – kann man keine ausreichende Analogie festmachen, um Ursachen besser verstehen zu können und diese Art der Manifetation von Gewalt (eben der gegen nichtmenschliche Tiere) zu bekämpfen. Damit bleibt aber auch der Genozid am Menschen ein vorwiegend gesondert zu behandelndes Phänomen.

Ausschließlich der Vergleich der Gewaltbereitschaft beim Menschen lässt Parallelen in den Täterpsychologien entdecken. Das hat mit dem jeweiligen Opfer aber nicht unmittelbar etwas zu tun. Warum „jemand“ zum Opfer wird, hängt mit schwer zu ergründenden psychologischen Ursachen auf Seiten des Täters zusammen. Wenn, als stereotypes Beispiel, ein betrunkener Mann einen anderen im Affekt wegen einer banalen Streitigkeit tötschlägt oder eine Frau Opfer einer Vergewaltigung wird, liegt in beiden Fällen zum einen der Aspekt der Gewaltbereitschaft des Täters vor, zum anderen aber wird ein Opfer aus völlig verschiedenen Motivationen heraus gewählt. Oder: als „Hexen“ im Mittelalter als solche klassifiziert und gefoltert wurden, lag eine andere Motivation zugrunde als bei Folterungen im islamischen Gewaltregime des Iran oder wiederum bei den Folterungen Oppositioneller in der Militätdiktatur Pinochets in Chile.

Der Umstand dessen, Opfer geworden zu sein, also des Verletztwordenseins des Opfers in seiner Würde als menschliches Individuum selbst, hat niemals Rechnung für die Tätermotivation zu tragen. Man kann die Gewaltmotivation nicht hauptsächlich über die Position oder Eigenschaften des Opfers ableiten, da das Opfer nur im indirekten Zusammenhang in ein Gewaltvergehen und in die Gewalt generell eingebunden wird. (Dabei sollte man nicht vergessen: es gibt keine ethische Grundsatzlegitimierung zur Gewalt, außer derer der Selbstverteidigung oder des Schutzes. Am deutlichsten ist die indirekte Einbindung eines Opfers in der Anwendung von Gewaltmitteln zur Erzielung politischer, ideologischer oder religiöser Macht.)

Ebenso würde man keinen direkten Vergleich zwischen der Strategie z.B. der Hexenprozesse zu der Struktur der Nazigewalt gegen ihre Opfer ziehen, weil die Komplexität der Formen von Gewaltbereitschaft in den spezifischen Fällen anders erklärt werden müssen.

Die Frage der Ursachen, der Psychologie des Täters und die Fragen der Gewaltstruktur sind maßgeblich für die Erklärung über die Motivation von Gewalt und ihrer Formation. Das einzige was eine generelle Schnittmenge darstellt, zwischen allen Formen der Gewalt, ist die Gewalt selbst.

Gewalt hat Ursachen und Folgen. Die Folgen müssen in einem differenzierten Verhältnis zu den Ursachen analysiert werden, da die Ursachen oft allein dem Täter (besonders auffallend im Fall von Persönlichkeitsstörungen (3)) oder einer Tätergruppe zugeordnet werden können, und die Folgen aber die konkrete (von Täter gewollte) Einbindung des Opfers in die Gewaltpsychologie des Täters anbelangen.

Das was nun die menschliche Gesellschaft nichtmenschlichen Tieren gewaltsam antut, braucht einen eigenen Begriff der dem Sachverhalt gerecht wird. Die Bezeichnung „Holocaust“ sollte als Bezeichnung klar umrissen bleiben: Das Wort an sich bezeichnete in religiösen oder rituellen Kontexten die überbleibende Asche oder vollständige Verbrennung eines Tieropfers! Das Wort hat heute die uns allen bekannte Bedeutung im Bezug auf den Menschenmord, vor allem an den Juden durch die Nationalsozialisten im Dritten Reich. Man hat bezüglich der Gefahr von Atomwaffen und den Abwurf der Atombombe auf Hiroshima auch von einem ‚nuclear holocaust’ gesprochen, und das Englische ‚holocaust’ wurde im angelsächsischen Sprachgebrauch häufig als Synonym für den Begriff Genozid – den Massenmord an Menschen durch Menschen – angewendet.

Es ist zweifelhaft ob es irgendeinen Sinn in der Sache der Tierrechte oder der Menschenrechte macht, eine Analogie durch den Begriff des „Holokaust“ aufzeigen zu wollen. Denn dieser Versuch der Gleichsetzung trägt weder zu einer weitergreifenden Erfassung der Problematik nichtmenschlicher Tiere in einer homozentrischen Welt bei, noch kann er wirklich die Ursache von Greueltaten die Menschen an Menschen begehen oder begangen haben klären.

Ich glaube, dass solange keine Übereinkunft in der Bezeichnung des Komplexes menschlicher Gewalt gegen nichtmenschliche Tiere besteht, man begrifflich weiterkommen könnte, indem man die Unbeschrieblichkeit und die Unfassbarkeit erstmal bestehen lässt. Man hat für das, was wir heute „Tiertötung“ und „Tiermord“ nennen, noch keinen ausreichenden Begriffsrahmen geschaffen und damit auch keinen eigenen umschreibenden Begriff zur Hand.

Abschließend: Es geht in diesem Text nicht darum, durch die Aufwertung oder vielleicht eher anders Bewertung der Tierproblematik, die Würde des Menschen in irgendeiner Weise in Frage stellen zu wollen. Sondern es geht darum, dass dem Problem der Gewalt gegenüber nichtmenschlichen Tieren in seinem eigenen Recht Aufmerksamkeit erteilt werden muss.

(1) Robert Nozick, Anarchy, State, and Utopia, New York: Basic Books, 1974, S. 36.

(2) Dieser Punkt würde so etwas wie ein Interspezies-Sozialverhalten anbelangen, das aber abgesehen von einigen wenigen Beispielen in der Tierrechtsliteratur bislang wenig Interesse gefunden hat.

(3) In Großbritannien führten Diskussion über die psychologische oder kriminelle Einstufung von ‚personality disorders’ vor forensischem Hintergrund zu dem Ergebnis, dass die Einstufung nicht-therapierbarer Persönlichkeitsstörungen für die Rechtsprechung ein nicht klar addressierbarer Problemfall bleibt.

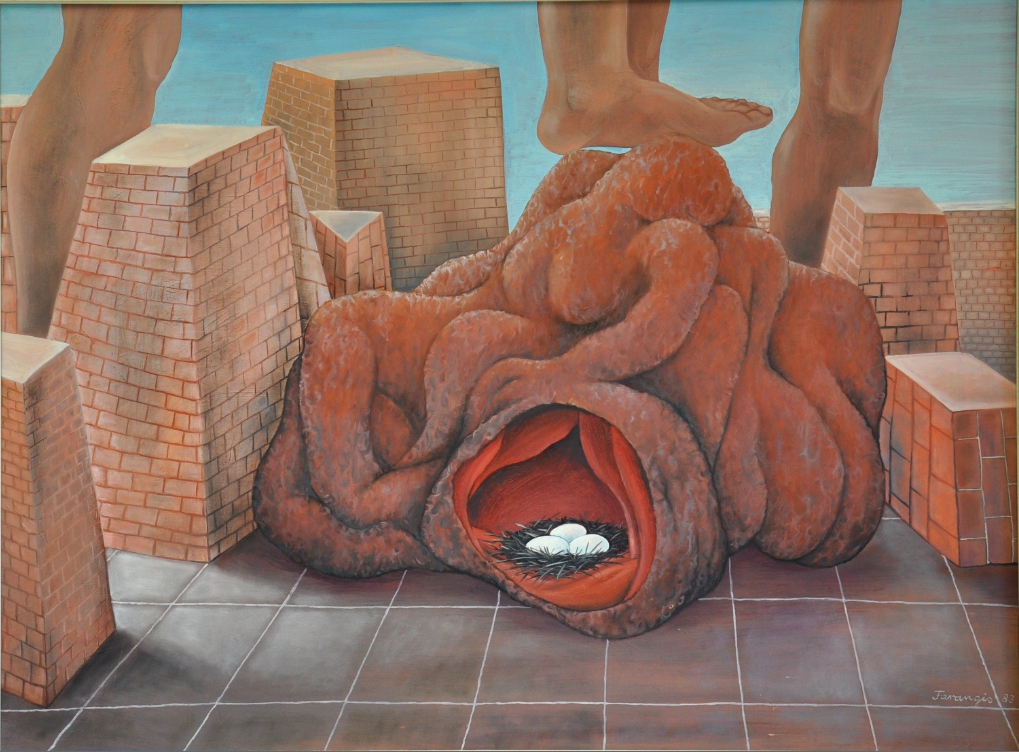

Das Acrylbild oben stammt von Farangis Yegane http://crownofthecreation.farangis.de/birds.one. Dieser Text wurde von Gita Yegane Arani-May verfasst und ist im Veganswines Reader 08 erschienen.

Dieser Text als PDF (öffnet sich in einem neuen Fenster)